# Android Platform Overview

# Objective

In order to build best-of-breed, native apps, it's critical that we understand the unique characteristics of each platform for which we plan to develop. In this section, you will examine the concepts, features, and components that identify Android apps.

# Contents

Android has a multitude of platform specific features that we need to be aware of as Titanium developers. Everything from its user interface components to its low level interfaces for Services and Intents make Android stand apart from other mobile operating systems. While Titanium's Javascript API does the lion's share of the work in terms of abstracting away these details, it's still very important to understand them in order to build high quality apps. The following content in this section will address each of the most important features of the Android operating system, as well as discuss how they are handled from the perspective of the Titanium API.

# User interface conventions

You will find quickly when researching Android that the UI can vary significantly among devices. While there is a standard, "vanilla" UI common to all Android operating systems, this is rarely seen on device. This is because Android is an open source, and thus extensible, mobile operating system. Mobile device vendors, like Motorola and HTC, are free to take the base UI and enhance it as they see fit. Android seeks to enable each vendor's own vision of what Android should be on their device, not dictate it.

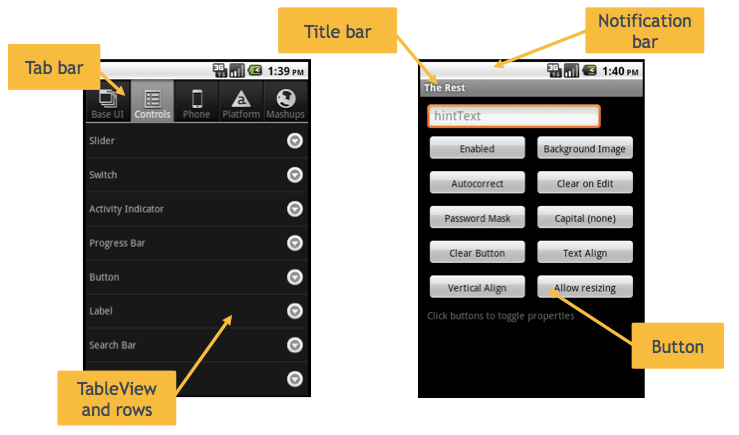

The following screens illustrate some of the common user interface components offered by the "vanilla" Android UI.

# Hardware buttons

Android devices feature four dedicated-function "hardware" buttons: Back, Menu, Home, and Search. Depending on the device, these buttons can be physical buttons or touch-based user interface buttons. The location and order of those buttons varies between device vendors.

Back – tap to return to the previous activity in the stack; if none remain in the stack you're returned to the home screen.

Home – return immediately to the home screen, pausing any currently opened apps

Menu – display a menu of activity-specific options

Search – display search functionality, either in-app or system-wide

The Home button behavior cannot be overridden, but you can interact with the Back, Search and Menu buttons.

To override the default behavior for the Back button, add an event listener for the Window.androidback event. (Prior to Release 3.0, this event was named Window.android:back. The older name is now deprecated.)

To receive an event when the Search button is pressed, add an event listener for the Window.androidsearch event. (Prior to Release 3.0, this event was named Window.android:search. The older name is now deprecated.)

You cannot directly override the Menu button, but you can customize the menu displayed when the user presses the Menu button. See Android Menus in the Android UI Components and Conventions section for more information.

# Screen sizes and densities

Android devices vary greatly in screen size and density. Screen size represents the physical size of the display. Measured diagonally, it can range from quite small (2.8 inches/71 mm) to large (4.3 inches/110mm) to tablet sizes (10.1 inches/256 mm). Android divides these into generally four categories: small, normal, large, and xlarge which are then denoted by their density-independent pixel measurements which Google labels "dp." Each density-independent pixel is equivalent to one physical pixel on a 160 dpi screen.

small screens are at least 426dp x 320dp

normal screens are at least 470dp x 320dp

large screens are at least 640dp x 480dp

xlarge screens are at least 960dp x 720dp

Aspect ratios vary as well, though Android generally lumps them into two buckets: long and "notlong" with the latter corresponding to devices with an aspect ratio not significantly different than the 320 x 470 "normal" screen.

Finally, density describes the actual pixels (aka dots) per square inch resolution of the screen. These range between:

ldpi screens are roughly 120 dpi

mdpi screens are roughly 160 dpi (this is the baseline "normal" density)

tvdpi screens are roughly 213 dpi

hdpi screens are roughly 240 dpi

xhdpi screens are roughly 320 dpi

xxhdpi screens are roughly 480 dpi

xxxhdpi screens are roughly 640 dpi

Titanium enables you to simply scale your user interface to fit the device's screen. But it also offers convenient features for specifically handling assets and layout for various screen sizes. You should plan to test on multiple devices if you want your user interface to be "pixel perfect" on all devices.

There is also a nodpi option where your images will not be scaled by the system if you do not want to create various assets for each density.

# Comparison with iOS

The Android user interface features some key differences that iOS users should note.

Tabs are at the top rather than bottom.

Window title bars don't include navigation buttons. Navigation functionality is provided by the hardware Back and Menu buttons instead.

The Navigation bar does more than just give battery and signal-strength info. It is the common location for system and app notification messages. Likewise, Android doesn't use the "badge" indicator like iOS.

# Application components

Android applications are built from the following components. Titanium shields you from some of the particulars, though it also gives you the tools to interact with these components when you want to.

Activities

Services

Intents

(We're simplifying things a bit here by ignoring content providers and broadcast receivers. Read Google's Android Fundamentals (opens new window) guide for more detailed information.)

# Activities

An Android app is made up of one or more activities. Each activity represents a "single screen with a user interface." For example, a window that lists messages in an inbox would be an activity. The window in which you read one of those messages would be a separate activity. The set of activities in an app work together to provide the functionality of that app.

On of the most powerful features of Android activities is that apps can start each other's activities. Let's say you want the user to be able to snap a photo within your app. You could write all the code to display the camera's live view along with the buttons that make up the photo-snapping experience. But with Android, you don't have to. The built-in Camera app has an activity that does all that already. All your app needs to do is launch the Camera app's activity and define what should happen with the data that's returned. Other apps can call on the activities that are defined within your app as well.

This shared-activity scheme is a key strength of the Android platform. Apps can share functionality, and they don't even need to know how those other apps work. Your app doesn't need to know how Camera's activity grabs the photo. You can just deal with the image that's returned. This activity sharing mechanism is what enables the "Share" button functionality included in many Android apps. This is discussed in more detail in the Intent section.

Each activity is listed in the AndroidManifest.xml file (opens new window). Notations in that file describe which activities are published (and thus available for other apps to call on). Titanium let's you create activities – a "heavy weight" window that corresponds to an Android activity. When the tiapp.xml file and your code is parsed by Titanium's compile scripts, appropriate entries are created in the AndroidManifest.xml file.

An Android Activity is not created until the "heavy weight" window is opened. Before the window is opened, the activity property refers to a plain JS object, which can be used to setup Ti.Android.Activity (opens new window) properties. Once the window is opened, the Android Activity is created, then the activity property can use the Ti.Android.Activity (opens new window) methods.

You'll find more info on the Android developer's Activity (opens new window) guide.

# Services

Services are "long running" app components that run without user interaction. You might use a service to periodically check a network resource or you play music while your app is in the background. Services are not separate threads or processes. They're not a way to offload work from your main application. You can create services by calling on Titanium's Ti.Android.Service (opens new window) module.

More information can be found at the Android developer's services (opens new window) page or the Ti.Android.Service (opens new window) page.

# Intents

Intents are messaging objects that hold data passed between activities, sent to or from a background service, or sent by system broadcasts. Intents enable your app to interact with the activities available on the user's device without knowing which apps the user has installed.

Earlier we stated that you can launch another app's activities. In truth, for security reasons your app can't directly start another app's activities. Instead, your app sends an Intent, which contains a URI to the content and instructions as to how it should be handled. You can create an explicit iIntent, in which you request that a specific activity be launched. If it's available, Android launches it for on behalf of your app. The more powerful option is to use an implicit intent, which will return a list of all apps available on a mobile device that are capable of handling your Intent.

Think back to the "Share" button functionality described earlier. Your app might publish some text via an intent, thereby sending a request for a list of all the apps that could handle that data. The OS would present a list of suitable apps to the user, who would choose which app to use. The user could select a Twitter client, email app, or any other app that can handle text. With properly formatted Intents, you can add large amounts of functionality to your apps simply by leveraging apps already installed on the device.

# Intent Filters

Intent filters are created through entries in the AndroidManifest.xml file. They are used to describe the types of Intents an Activity can accept. Android uses intent filters to determine which activities can respond to an intent. For example, this is how Android narrows the list of all possible apps to just those shown on a particular Share menu. See the Android docs (opens new window) for more information.

More information about intents and intent filters are available from the Android docs (opens new window) or the Titanium Android module (opens new window) page.

# References and further reading

Google's Android Fundamentals (opens new window) document is recommended reading

# Summary

In this chapter, you learned about some of the characteristics that define Android and Android apps. You looked at user interface components, device buttons, and application components, such as activities and intents. Next we'll learn what makes iOS unique from other mobile operating systems, and how we can leverage these features with Titanium.